#179: Pinocchio

Release Date: February 23rd, 1940

Format: Theater (New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles, CA)

Written by: Aurelius Battaglia, William Cottrell, Otto Englander, Erdman Penner, Joseph Sabo, Ted Sears, and Webb Smith

Directed by: Hamilton Luske and Ben Sharpsteen

4 Stars

Watching a matinee this afternoon of a pristine 35mm print of Disney’s Pinocchio, some 85 years after its release, I was struck by the illusionary magic of cinema.

It might be cliche, but I think we often forget just how magical movies are, especially now that we’re decades into the digital age.

You know those things on the screen don’t actually move, don’t you? It’s fun to remind yourself that it’s nothing but individual images, each slightly different than the one before and the one after, that are transferred to film, put on a reel, and run in front of a light bulb at 24 frames per second. Make the sequence of these thousands of images beautiful enough, and you can move human beings to tears, to laughter, to love. You can change their lives.

Walt Disney understood this, as much as anybody.

His film, Pinocchio, is a wonder. I hadn’t seen it since I was a child, and even then I’d only seen it a couple of times. Watching it today, I was shocked at how much I remembered of the film. It must have made that big of an impact on me all those years ago.

It might be the film’s subtexts that stuck to me. It’s a fascinating movie that trusts its audience, even the young ones, to weather dark and oftentimes confusing subject matter. In that way we are much like Pinocchio himself. We don’t fully understand this world in which we find ourselves, and we are vulnerable to being led astray, to being taken from our home and family, which is a child’s worst nightmare.

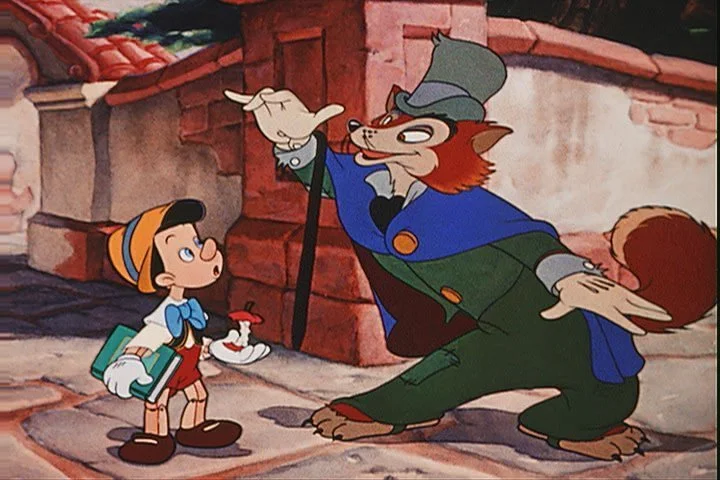

Take, for example, Honest John (my favorite character). He’s the shady con man who tricks Pinocchio into skipping school and then sells him into Stromboli’s traveling circus as his star attraction: The Amazing Puppet Without Strings! It’s remarkably odd, and a bit disturbing, that Honest John is not a human, but rather a human-sized, anthropomorphic fox. How strange. Pinocchio takes place in a human world (more or less), but Honest John is an animal.

Why?

This is the subtext that seems to be targeted at a child’s psyche. Honest John is a predator, literally, an animal without human empathy. Whether a child consciously knows it or not, he serves as a form, a symbol, of something that should be feared. A representation of something in which a child is defenseless. He’s a strange, predatory beast that can whisk you away into the deep, dark woods.

But what makes Pinocchio an endearing classic, all these years later, is that it is also a film that knows how to lead its audience back home. Despite the Honest Johns and the Strombolis and the Lampwicks and the Monstros of this strange, confusing world, Pinocchio ends up being a joyful tale. It’s a story of fate and love.

It reminds us that if we stay true to who we are, if we wish upon a star, our dreams come true.